While Kenya has advanced its democratic processes, the 2013 election exposed major technological shortcomings.

It was a landmark occasion for Kenya, Africa, and the global community when, on March 9, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) declared Uhuru Kenyatta—son of Kenya’s founding president, Jomo Kenyatta—the country’s fourth president.

Yet, nearly three weeks later, the election’s outcome remained contested. Raila Odinga, Kenyatta’s primary challenger, petitioned Kenya’s Supreme Court to invalidate the IEBC’s declaration. Odinga’s case hinges largely on the failure of technology during the election.

International observers like the European Commission acknowledged [PDF] that although technology faltered, the voting process was overall transparent and reflective of public will. Kenya has indeed enhanced its democratic credibility and electoral transparency. While it’s true that IT systems malfunctioned during the vote due to under-preparation and insufficient testing, the country’s democratic institutions held strong. With the official count based on manual ballots, procedural integrity proved more vital than the technical tools.

Though Kenya has conducted elections for decades, only the 2002 and 2013 elections were broadly viewed as fair. The 2007 election was marred by a disputed result between President Mwai Kibaki and Raila Odinga, igniting violence that killed over 1,400 people and displaced hundreds of thousands. In the aftermath, Kenya worked to address ethnic divisions and reinforce democratic systems. Expectations were high for the 2013 elections to be both peaceful and credible.

Judiciary Reviews Election Disputes

Leveraging Technology for Better Voting

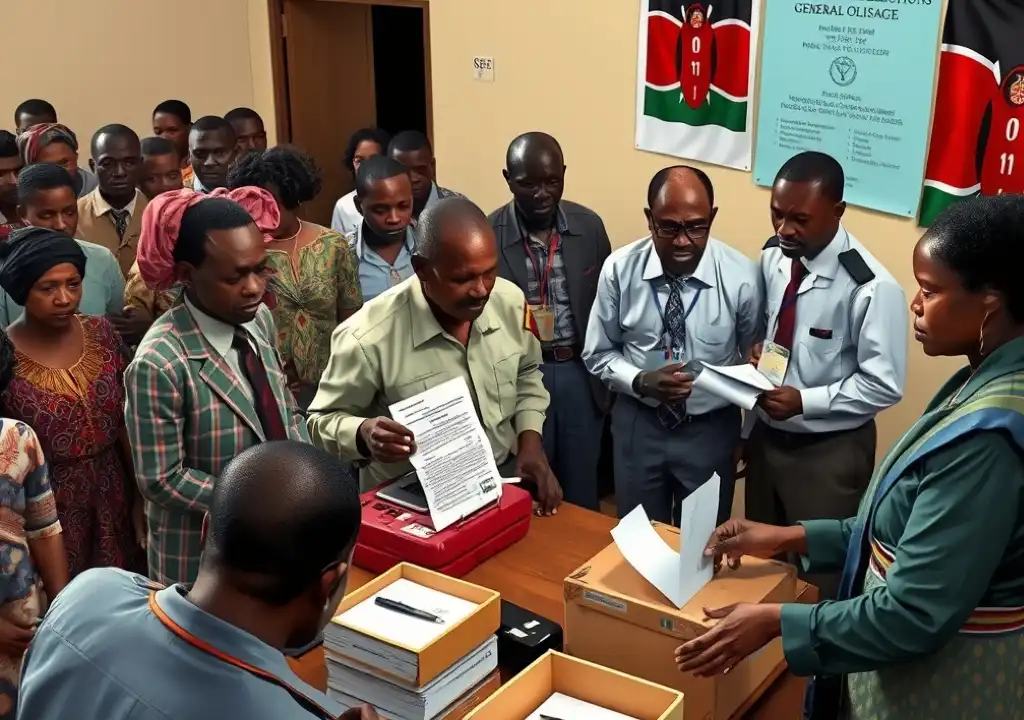

Following the 2007 crisis, the Kenyan government introduced more advanced technologies in the 2010 referendum and several by-elections to rebuild electoral trust. The 2013 elections were intended to represent a peak in the use of technology. Two main innovations were introduced.

First, a Biometric Voter Registration (BVR) system, which cost $95 million, was implemented to secure a credible voter registry. Over a 30-day period in late 2012, more than 14 million Kenyans registered. At each polling station, this register was accessible both electronically—via Electronic Voter Identification devices (EVIDs)—and in printed form, both designed to authenticate voters.

Second, the IEBC aimed to use electronic systems to transmit preliminary vote counts from polling stations. These results would be backed up by physical delivery for the official tally. Technical support for this plan was provided by IFES, funded by USAID.

However, the election day was riddled with technical breakdowns. EVID Poll Books widely failed due to dead batteries and lack of power in remote polling stations. Phones designated to transmit results malfunctioned due to connectivity problems, low battery, and password issues. Eventually, the national tallying center’s servers crashed. The IEBC had to halt electronic reporting and revert to receiving paper Form 36 submissions from returning officers.

These failures highlight two major missteps: late procurement of essential equipment and inadequate pre-election testing. With regular power outages in Nairobi and limited rural infrastructure, failure to plan for backup systems was a critical oversight. The rushed acquisition of phones and biometric tools—just a month before the vote—meant they were never properly stress-tested. Professor Makau Mutua questioned whether the failures were rooted in incompetence, poor digital literacy, or a lack of foresight. Most signs point to unpreparedness and ignored expert advice.

Toward Systemic Reform

Even with major technological issues, the election’s core integrity appeared to remain intact. The manual vote count stood as the official record. Voters were properly verified using printed registries. At the station level, results weren’t finalized without consensus among officials and party agents. This procedure was repeated at the constituency level in full view of observers and party representatives. Ballots—used and unused—were sealed and transported securely to ensure transparency and traceability throughout the process.

Globally, hybrid voting systems—mixing paper trails with digital speed—are considered best practice. A 2004 symposium at Harvard Kennedy School [PDF] noted that digital-only systems often produce complex, hard-to-diagnose failures. Paper ballots, on the other hand, offer a tangible and reliable audit path. Kenya’s 2013 vote reinforced this point.

The 2013 election offers important takeaways for scholars and democracy advocates. First, transparent and inclusive processes with well-documented procedures are crucial. Second, technology must be rigorously tested ahead of elections. Third, collaboration between government and civil society can build resilient institutions staffed by competent officials. Finally, the 2010 Constitution has helped build these institutions, improving election quality.

Post-2010, Kenya’s democratic frameworks have matured. The judiciary has gained credibility, and groups like the Carter Center were invited to observe the elections. While IT fell short, democratic governance advanced. The root of the word “technology,” techne, once meant the skill to complete a task. In that sense, Kenya’s institutional knowledge represents a form of political technology in its own right.

The final verdict of this election lies with the Supreme Court. The ruling will be watched closely both within Kenya and internationally, as it has the potential to either bolster or erode public faith in the democratic process. The Court’s decision to re-tally votes from 22 polling stations is a critical step toward reinforcing that trust. Ultimately, the real test will be how Kenyans respond to the judgment—regardless of the winner.

About the Authors:

Dr. Warigia Bowman holds a doctorate in public policy from Harvard and has taught in Kenya and Egypt. She now teaches at the University of Arkansas and focuses her research on IT and democracy in East and North Africa. She served as an accredited observer during the 2013 Kenyan election.

Brian Munyao Longwe is a seasoned Kenyan tech expert involved in establishing internet infrastructure across Africa and parts of Asia. He currently consults independently, helping bridge tech, government, and startups.