The sense of community Apple helped nurture in cities like Cairo and Tunis is an integral part of Steve Jobs’ legacy.

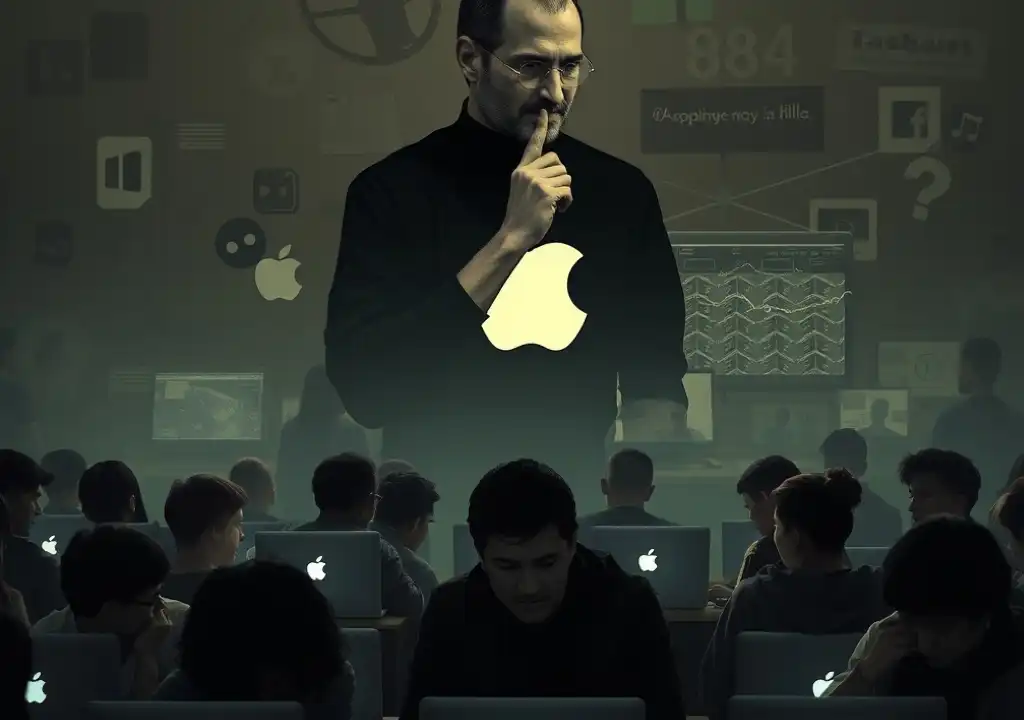

In creative fields, it’s difficult to overstate the significance of Steve Jobs’ passing. For many artists, musicians, designers, and other professionals I’ve encountered over the past two decades, owning an Apple product has been an essential element of becoming a legitimate artist. Apple has deeply embedded itself into our identities.

Using a Mac seemed to enhance creativity, whether you were composing a song, creating a movie, designing a website, or writing a novel. It felt like a performance-enhancing drug for creatives.

While this notion lacked factual grounding—since the same programs could run on both Macs and Windows PCs—working on a Mac made you feel elevated, smarter, and more talented. It was like using a Gibson Les Paul or a Fender Stratocaster guitar: other guitars could do the job, but they didn’t quite reach the same level. The limitations of other devices often became apparent just when you needed them to perform at their best.

The Creative Essence of Apple

An Apple product resembled an Ikea desk or bookcase. Although Ikea launched its first U.S. store a year after the Macintosh’s debut, it offered a more affordable and accessible design.

However, unlike Ikea, an Apple product never felt like just another mass-produced item. It was a personal experience, showcasing modernist design principles—simplicity, beauty, and functionality—all harmonizing to create an intuitive user experience. Jobs’ design genius was so ingrained in his products that it felt like they amplified your own creative potential.

Of course, such beliefs may have been idealistic. If anyone should have been a prime target for hackers and virus developers, it was Steve Jobs and Apple. Yet, Jobs’ company projected an image that embodied the zenith of modernist consumer style, akin to Bauhaus for the computer age, while also aligning with countercultural ideals and the Hacker’s Manifesto. Using Apple products—whether computers, iPods, iPhones, or iPads—felt like stepping into a world of boundless potential.

Counterculture and Corporate Paradox

The introduction of the Macintosh through the iconic “1984” advertisement during the Super Bowl—a prime example of corporate consumerism—seemed like a bold act of rebellion. Jobs used this mainstream event to promote a product that directly challenged corporate America, drawing inspiration from George Orwell’s “1984” without obtaining a license to do so—an act of piracy in the hacker tradition.

Years later, Apple has become the most valuable corporation globally. Despite once being an underdog against IBM and Microsoft, the myth of Apple as a countercultural icon emerged as one of Jobs’ greatest successes. In reality, Apple was always a corporation focused on maximizing profits. Jobs, inspired by figures like Sony’s Akio Morita, learned how to charge a premium for well-designed, high-quality products while mass-producing them for profit—the ultimate success in consumer capitalism.

Unfortunately, the workers who produce Apple’s products, often subjected to exploitative conditions, face a grim reality, with some driven to desperation by low wages and grueling work environments, leading to tragic outcomes like suicides.

The Aura of Apple Products

Apple’s greatest success lies in its ability to harness the paradox of modern cultural production identified by the Frankfurt School theorists after World War I. These theorists recognized that commodified culture was an essential tool for reinforcing the status quo, but also a double-edged sword.

Walter Benjamin, a key figure in this critique, argued that mechanical reproduction stripped the aura from art—its unique, intrinsic value. He saw this as a good thing, as it opened the door to art that could challenge totalitarian ideologies like fascism and capitalism.

In contrast, Theodor Adorno viewed mass-produced culture negatively, believing it lacked the power to reveal societal contradictions. Style, he argued, promised more than it could deliver.

Whether or not Jobs was familiar with Benjamin and Adorno’s work, Apple succeeded because its products seemed to restore the aura to cultural creations. Rather than reinforcing societal obedience, as Adorno suggested, Apple products empowered individuals to “think different,” initiating the first steps toward social liberation. However, the aura created by Apple’s design often obscured the exploited labor behind these products.

The myth of Apple as countercultural led consumers to believe they were challenging the system, while in reality, they were reinforcing it. At the same time, Apple’s aesthetic appeal enabled users to experience greater freedom, both personally and professionally.

Spreading Influence in the Middle East

Apple products were once rare in the Arab world due to high import tariffs, but by the mid-2000s, the region began to embrace Apple laptops, especially in the arts, design, music, and film sectors. This was around the same time that the “Facebook generation” began to question the long-standing political regimes in the Arab world.

In 2011, during the protests that ousted Mubarak in Egypt, Apple products played a pivotal role in activism. Dozens of Macs circulated in a safe house in Cairo, where young activists used them to write articles, upload videos, edit films, and communicate with the world. The shared sense of purpose and creativity was palpable, and the Apple devices provided both practical and symbolic value in this revolutionary space.

Although the type of computer used didn’t directly affect the success of the revolution, there was something undeniably reassuring about the glowing Apple logos in the darkened rooms of Cairo’s activists. The aura of Apple devices fostered a unique sense of community and connectivity, binding the activists together even amidst the chaos.

While it’s hard to imagine the revolution being as seamless on Windows-based systems, Apple computers became a symbol of the activists’ defiance against the oppressive regime. Jobs likely never envisioned his products being integral to political revolutions, but Apple’s role in movements like the Arab Spring and the Occupy Wall Street protests in the U.S. is a testament to their enduring influence.

Let’s hope that one day, Apple’s products can also contribute to improving the lives of the exploited workers who create them.

Mark LeVine, a history professor at UC Irvine and senior researcher at Lund University in Sweden, explores these themes in his recent works, Heavy Metal Islam and Impossible Peace: Israel/Palestine Since 1989. These views are his own and do not reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.