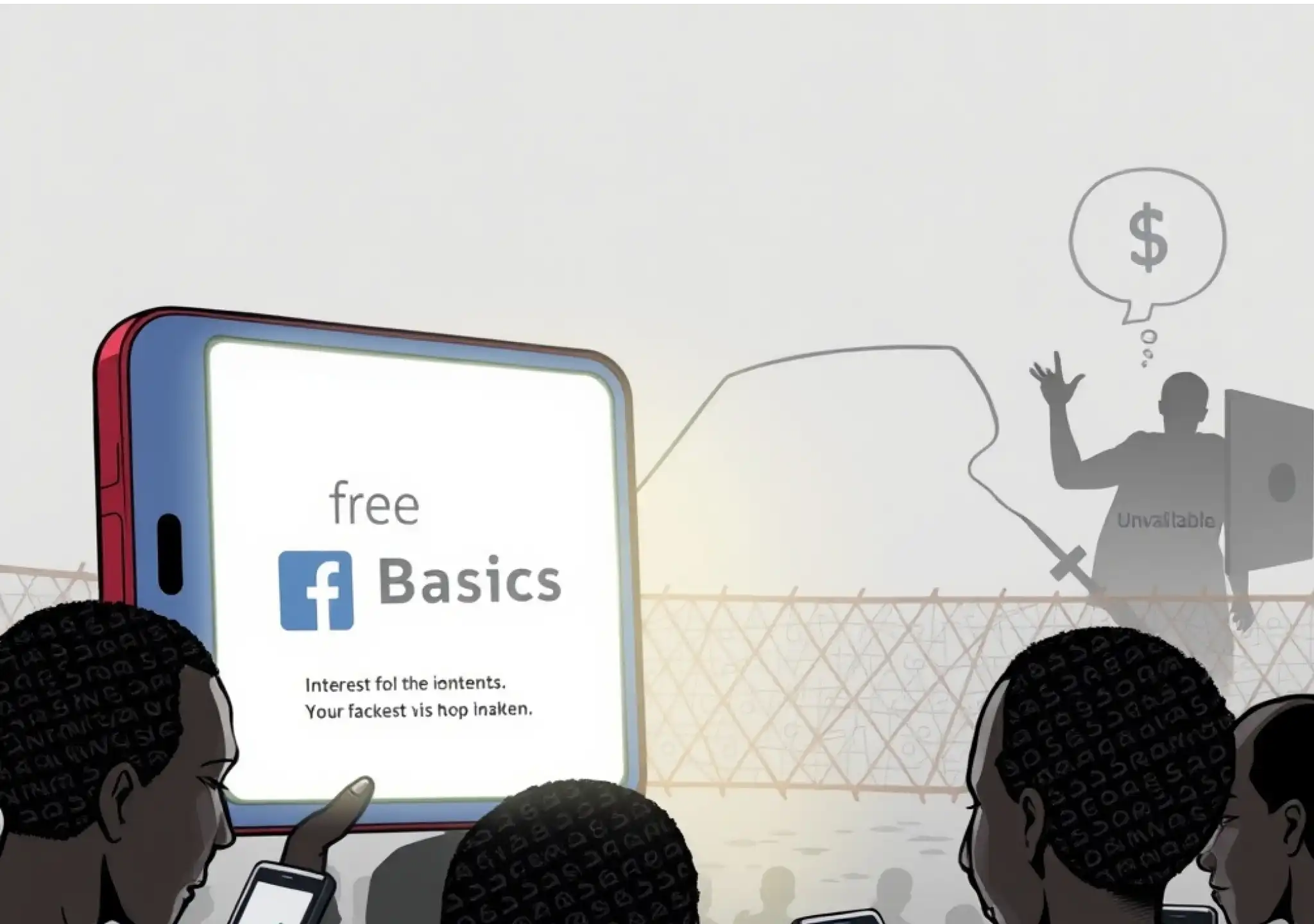

Facebook’s Free Basics app, designed to provide free access to select online services in developing nations, does not live up to its promises.

In many African countries, the high cost of internet access remains a barrier for most people. For them, affordable or free access to essential digital information can be crucial. Facebook launched Free Basics in 2015 as a solution to this challenge. CEO Mark Zuckerberg praised it as the “first step towards digital equality,” aiming to bring millions from countries like Ghana and Kenya online.

Free Basics offers limited internet access via mobile phones, allowing users to view only a curated list of websites, including Facebook. It doesn’t support external links or video playback—but for those without alternatives, it may seem better than having no access at all. For instance, even limited access to public health updates can have life-saving implications in sub-Saharan Africa.

A Heavily Filtered Internet Experience

Despite being free of charge, Free Basics carries hidden costs, including concerns raised by digital rights advocates. The app limits users to a small selection of websites, violating principles of net neutrality. Additionally, it gathers user data without clear disclosure about how that information is utilized.

Though Facebook promotes the app as a gateway to the broader internet, what it really offers is a restricted environment tailored more for data collection than for user empowerment or education.

Research Reveals a Gap Between Promise and Practice

This past spring, five researchers from the Global Voices citizen media community, based in countries such as Colombia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Mexico, conducted a three-month study using Free Basics. Their findings revealed a stark contrast between Facebook’s claims and the app’s real-world utility.

The app demonstrated little awareness of local cultural or informational needs, lacked comprehensive features, and engaged in extensive data collection. Ultimately, Free Basics failed to deliver meaningful value to the low-income users it claims to support.

Failing to Deliver Local Value

Free Basics promotes itself as a tool to provide crucial content for free. However, it often fails to include the kinds of resources that would truly benefit its users.

In both Kenya and Ghana, countries with rapidly growing tech and online content sectors, Free Basics offered minimal access to this local digital ecosystem. In Kenya, only three of the 16 featured services were local—two were job search platforms and the third, the Daily Nation newspaper. All were only available in English.

This is surprising given Kenya’s high mobile internet speed—ranking 14th globally and even outpacing the U.S.—and its thriving digital content scene. For example, Kenyan blogs like Farmerstrend, Kuzabiashara, Healthkenya, and Mzalendo provide valuable local insights on farming, health, governance, and more, yet none are featured on the app.

Additionally, important government service sites like eCitizen or Huduma Kenya are missing from the app, even though they provide vital services ranging from registering businesses to applying for identification documents.

The situation is no better in Ghana, where Free Basics also lacks access to key local content and government services. About 70% of the included websites originate outside Africa and are often irrelevant to local users.

Popular Ghanaian news platforms such as myjoyonline.com, citifmonline.com, and adomonline.com were also absent. Even when some news sites appeared, users couldn’t read the full articles, view photos, or watch videos unless they paid for additional data. This limitation risks increasing misinformation by only showing partial or incomplete content.

In some app versions, websites were not categorized meaningfully—users had to scroll alphabetically through unrelated services, and some versions lacked a search feature entirely.

Lack of Language Support

Free Basics also falls short in meeting the linguistic needs of its users. In Kenya, while the app can be used in Kiswahili, only three services are available in that language. Although English is an official language, Kiswahili is more widely spoken by the majority of the population.

In Ghana, the version of Free Basics offered through the provider Tigo was exclusively in English, with no option to switch to widely spoken local languages like Twi or Hausa.

Exploiting User Data for Profit

Free Basics includes four different privacy and terms-of-use policies. These appear only as faint grey text beneath a bright purple “continue” button, which users must click to enter the app. Even for experienced users, distinguishing between Free Basics’ own policies and Facebook’s broader terms proved challenging—raising concerns about transparency for first-time internet users.

Although Facebook claims it uses separate data policies for non-Facebook services within Free Basics, the underlying technology still enables it to track users’ behaviors, including which sites they visit and their phone numbers. This data helps Facebook refine its advertising strategies in developing markets—clearly positioning user data as a commercial asset.

While Facebook insists that Free Basics is about introducing people to the internet, the app seems more focused on capturing user data than on fostering real digital inclusion.

In the end, Free Basics may look like a generous gift—but it’s one that keeps giving back to Facebook.